Anne Puckridge served as an intelligence officer during the second world war before working in various jobs and raising a family. But, as a result of being “cheated” out of her full basic state pension by the UK government, the 93-year-old has been left so hard-up she has to think twice about going to the supermarket or buying Christmas presents for her grandchildren.

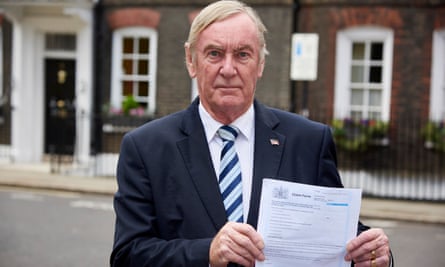

Meanwhile, at 87, widower Alan Job has been forced to find paid work – because, he says, the government’s decision to freeze his state pension means he is now unable to meet his normal living expenses.

He has been offered a 20-hours-a-week position with an animal charity.

Puckridge and Job are just two of about 550,000 Britons living overseas losing out as a result of the UK’s “frozen pensions” policy. Their basic state pensions don’t increase every year, as in the UK – they are permanently frozen at the date the individual retired or arrived in their country of residence.

Puckridge’s daughter Gillian Mittins started a petition on the Change.org website to highlight their plight – and has seen it take off dramatically. At one point her petition was notching up roughly 100 signatures a minute and, as of Friday lunchtime, had been signed by about 175,000 people. Mittins says her mother has been “punished” by the British government for deciding, at the age of 76, to move to Canada to be close to her family. If she had stayed in the UK, she would be receiving up to £125.95 a week (the full UK basic state pension). Instead, it is frozen at the 2001 level of £72.50.

“This is despite the fact that by living overseas, she is saving the British government thousands of pounds each year in medical costs, bus passes, social services and other benefits,” says Mittins.

Guardian Money has calculated that the total amount Puckridge has missed out on between 2001 and now is more than £22,000.

Campaigners say cases like this highlight the unfairness of the UK policy. There are more than 100 countries worldwide where the UK basic state pension is not “uprated” each year, including Australia, Canada, South Africa and New Zealand.

If you move to one of them, your UK pension will be permanently frozen at the date you retire, or when you arrived, no matter how rich or poor you are, what job you did, or how much national insurance you have paid.

But if you move to an EU country, the US, or one of a seemingly random list of places, including Macedonia and Samoa, your state pension increases in line with inflation.

The policy has been in place for decades, and ministers have conceded the rules are “illogical”. However, they argue it would be too expensive to uprate those affected, and that the priority should be targeting money at the poorest pensioners at home.

Ministers have estimated that to fully uprate everyone’s frozen pensions to current levels would cost more than £500m a year. However, campaigners say that so-called “partial uprating” would involve a much lower upfront cost: £37m.

Puckridge served with the Women’s Royal Naval Service (the Wrens) during the war, after which she returned to the UK and brought up her family, working in administrative jobs and, later, as a lecturer in Stroud, Gloucestershire. At retirement age she continued to work part-time until 76, when she relocated to Canada to be closer to her daughter and grandchildren.

“My mother served her country, then she spent the rest of her working life paying national insurance. She expected, like the rest of us, that when it was time to retire, she would be able to access the pension she had paid into,” says Mittins.

She adds that many vulnerable overseas pensioners have been forced to return to the UK, leaving their family behind, because they can no longer cope with the real value of their pension being eroded. “Please sign this petition, for my mum and for all the other overseas pensioners who are being cheated by the British government,” is Mittins’s plea.

Meanwhile, Alan Job and his family relocated from Birmingham to South Africa in 1972. Their eldest daughter suffered from asthma, so they thought a change of climate would help.

It did, so they stayed, but they maintained their British citizenship and continued paying into the UK state pension. At 65, Job started drawing it. He received £63.60 a week, while his wife – who died in March this year aged 87 – received £44.99. “Our pensions remained the same in pounds, with not one penny extra for the 22 years,” says Job, who lives in Durban.

When he notified the British pensions authority of his wife’s death her pension was cancelled but he was told his would be upgraded. “Imagine my surprise, shock and disgust when I found my increase was just £8.18 per week,” he says. “Is that all they think my wife of 57 years was worth? My/our joint pension has dropped by £36.81 a week. As a result, I was unable to meet my normal living expenses, and have had to seek employment. How many 87-year-old pensioners in Britain, or ‘unfrozen’ countries, have had to do that?”

He will earn the equivalent of about £40 a week at the charity.

The Department for Work and Pensions has previously said that overseas recipients of the basic state pension will only get a yearly increase if they live in the European Economic Area (EEA), Gibraltar or Switzerland, or in a country with a reciprocal agreement with the UK that allows this to happen.

Find out more about the campaign at endfrozenpensions.org

How Guardian Money exposed the scandal

April 2002: “Heat’s on for pension freeze... The amount paid depends on where you live, but this policy is under fire...”

May 2012: “The 100-year-old woman whose state pension is frozen at just £6 a week... Is there an expat pensioner who is getting a worse deal than 100-year-old Annie Carr?”

March 2014: “Retiring abroad? Don’t catch a cold because of the state pension freeze... Pension rules mean that Geoff Amatt, aged 100, was never able to move to Canada to join his only daughter.”

June 2016: “Frozen pension: the RAF veteran facing a chilling choice in Canada... At 90, Joe Lewis could return to the UK for his full state pension - without his sick wife, who’s in care. Or he could sell his home to try and make ends meet.”

March 2017: “The Falklands war hero fighting for his state pension... Roger Edwards served as a navy officer in the Falklands, and retired there. Now he feels betrayed by the UK government.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion